Canadian Aboriginals need justice, not tributes

Talk About Race — By Mike Barber on February 16, 2010 at 08:00The 2010 winter Olympics kicked off in Vancouver, British Columbia with its opening ceremonies on Friday, February 12, 2010. Being perhaps one of the least athletically-minded people on the planet, I wasn’t even aware the ceremonies were happening until comments started flooding my Twitter timeline. I would have ignored the tweets were it not for the praise people were giving for my country’s tribute to our indigenous peoples, which immediately started to give me the creeps. Let me explain…

The Aboriginal peoples of Canada are comprised of three groups: First Nations, which is actually comprised of hundreds of distinct nations or bands (such as the Mohawk Nation and the Algonquins, for example); the Inuit, who inhabit the Arctic and subarctic regions of Canada (no, they are not “Eskimos”); and the Métis, who are of mixed Aboriginal and European (mostly French) ancestry. According to the 2006 Canadian Census, the Aboriginal population of Canada is 1,172,790, which makes up 3.8% of Canada’s population of 31,612,897. The Census counted 698,025 First Nations people which is 59.5% of the Aboriginal population and only 2.2% of the overall Canadian population.

credit: Ansgar Walk

The opening ceremonies were indeed a beautifully choreographed and brilliantly executed event, and the inclusion of Canadian indigenous culture in the ceremony is not the only place where Aboriginal culture is being featured in the winter Olympics. The logo of the 2010 Olympics contains the Inuksuk, which has deep cultural roots for the Inuit people. With all this tribute to Canada’s first peoples, you would think Canadians in general have a deep respect and love for them and their culture. The truth is that all this “inclusion” is right in line with Canada’s theme of parading multiculturalism and Aboriginal heritage when it suites us to do so.

I might have been able to enjoy the exhibition if not for the fact that Canada has very serious issues when it comes to the treatment and attitude towards its Aboriginal people. According to Phil Fontaine, the former national chief of the Assembly of First Nations, “As far as Aboriginal people are concerned, racism in Canadian society continues to invade our lives institutionally, systematically, and individually.” For example, the First Nations peoples suffer disproportionately higher rates of poverty, unemployment, and incarceration; substance abuse and suicide rates in some areas, such as the northern coast of Labrador, are so high they qualify as epidemics. The general attitude of Canadians is classic blaming the victim; no consideration is given to the systemic abuse the Aboriginal community has historically been subjected to.

Whenever a group of Aboriginals engage in any non-violent action of protest to bring attention to their struggle, the op eds and letters to the editor more often than not express opinions ranging from mild disapproval—criticizing their “confrontational” tactics while being obtuse to the fact that more diplomatic or litigious tactics had already been tried and failed—to outright racist vitriol—typically characterizing Aboriginal people as drunk, lazy ingrates living off of welfare, etc. Even some of my more progressive, liberal-minded acquaintances have made blanket comments about Aboriginal people that left me both stunned and embarrassed for all involved.

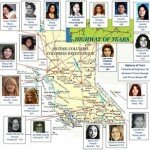

In northern British Columbia, there is a 716-kilometer (445-mile) section of the Trans-Canada highway that runs between Prince George (near the Rocky Mountain Trench) and Prince Rupert (which is just south of the British Columbia-Alaska border) that has come to be known as the “Highway of Tears.” Since 1969, at least 32 women—many of whom are Aboriginal—have been killed or have suspiciously disappeared along this stretch of road. For decades, these deaths and disappearances have received minor if any interest from law enforcement. This is just one instance of the systemic absenteeism and institutionalized racism Canada’s Aboriginals have had to deal with for a very, very long time.

In northern British Columbia, there is a 716-kilometer (445-mile) section of the Trans-Canada highway that runs between Prince George (near the Rocky Mountain Trench) and Prince Rupert (which is just south of the British Columbia-Alaska border) that has come to be known as the “Highway of Tears.” Since 1969, at least 32 women—many of whom are Aboriginal—have been killed or have suspiciously disappeared along this stretch of road. For decades, these deaths and disappearances have received minor if any interest from law enforcement. This is just one instance of the systemic absenteeism and institutionalized racism Canada’s Aboriginals have had to deal with for a very, very long time.

With all that in mind, you will have to forgive me for being a “party pooper” when it comes to this so-called tribute. While a beautiful spectacle it may be, it’s little more than lip service. The only time Canada really seems to care about the First Nations, Inuit and Métis is when it serves the national self-image. You may think me cynical, but this little dog and pony show is nothing more than a farce unless it can lead to serious consideration for the justice and needs of the Aboriginal people.

Tags: aboriginals, canada, Culture, First Nations, indiginous, Inuit, Metis, Olympics, VancouverAuthor: Mike Barber (9 Articles)

Mike Barber is an independent filmmaker with a particular interest in issues surrounding social justice. He is currently directing “A Past, Denied: The Invisible History of Slavery in Canada,” a feature documentary exploring how a false sense of history—both taught in the classroom and repeated throughout the national historical narrative—impinges on the present. It examines how 200 years of institutional slavery during Canada’s formation has been kept out of Canadian classrooms, textbooks and social consciousness. He is currently based in Toronto, Ontario. You can follow him on Twitter at http://twitter.com/mike_barber (@mike_barber) and his film at http://twitter.com/apastdenied (@apastdenied)

Share This

Share This Tweet This

Tweet This Digg This

Digg This Save to delicious

Save to delicious Stumble it

Stumble it

Racial Profiling – Not Just for Middle-aged Elite University Professors Any More!

Racial Profiling – Not Just for Middle-aged Elite University Professors Any More! Haiti and the broken promises

Haiti and the broken promises Why immigrant rights advocates need to understand history

Why immigrant rights advocates need to understand history

1 Comment