See no race, see no gay

What proponents of a gay-blind approach to bullying in the Schools can Learn from Race Relations

Co-written with Nestor L. Lopez-Duran PhD, Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of Michigan,

Pssst…… Refusing to acknowledge differences won’t make them go away.

Over the past few weeks, we have been inundated with stories of bullied and shamed young people taking their own lives due to the hostile environment of socially sanctioned hate.

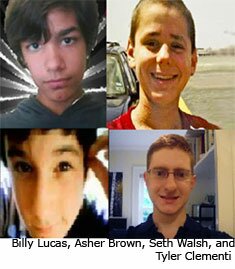

Just this September three teens committed suicide after experiencing severe bullying: 15-year-old Billy Lucas of Indiana, 13-year old Asher Brown of Texas, and 13-year-old of California. All three teens were self-identified as, or perceived by their classmates to be, gay. Also in September Tyler Clementi, an 18-year -old freshman at Rutgers University, committed suicide after his roommate video taped him having an encounter with another boy and streamed the video over the internet to other students, and 19-year-old Zach Harrington committed suicide after attending a homophobia-filled City Council meeting in Norman, Oklahoma, where his neighbors opposed the designation of October as Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgendered History Month.

Just this September three teens committed suicide after experiencing severe bullying: 15-year-old Billy Lucas of Indiana, 13-year old Asher Brown of Texas, and 13-year-old of California. All three teens were self-identified as, or perceived by their classmates to be, gay. Also in September Tyler Clementi, an 18-year -old freshman at Rutgers University, committed suicide after his roommate video taped him having an encounter with another boy and streamed the video over the internet to other students, and 19-year-old Zach Harrington committed suicide after attending a homophobia-filled City Council meeting in Norman, Oklahoma, where his neighbors opposed the designation of October as Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgendered History Month.

However, despite the recent media attention to this issue, the bullying of gay teens and the resulting high rates of suicide among them, have been major problems for years. This led Congresswoman Linda Sanchez (D-PA) and Senator Bob Casey (D-PA) to introduce the Safe Schools Improvement Act (SSIA), which would require schools receiving federal funding to implement policies to explicitly prohibit bullying on the basis of the “student’s actual or perceived race, color, national origin, sex, disability, sexual orientation, gender identity, or religion”.

The SSIA received strong opposition from religious organizations who objected to the inclusion of sexual orientation as a protected target group. For example, the lobbying organization Focus on the Family argued that this bill would “open the door to teaching about homosexuality as early as kindergarten. And it would lay the foundation for codifying sexual orientation and gender identity as protected classes,” which they oppose.

The opposition to the SSIA appears to be at least partially based on the premise that the SSIA should not include any protected categories, since such inclusion would discriminate against those who are not members of the protected classes. Essentially, they promoted limited mention of the factors that were the basis of the bullying. The notion that being color-, race-, gender-, or gay-blind would better combat the underlying causes of discrimination rather than explicitly calling out the root issue is highly reminiscent of the arguments presented by conservative organizations when opposing efforts to combat racial discrimination.

Although on the surface this call for blanket anti-bullying campaigns, essentially a gay-blind approach to combating discrimination, might seem sensible, research suggests that ignoring the underlying characteristics that places someone at risk for discrimination can actually can make the problem worse. A clear example of this fallacy comes from the idea that being “colorblind” at the personal and institutional level can help eliminate racism. Research suggests that this idea is wrong. Being colorblind is actually quite problematic and does not meet the results it claims to seek.

The colorblind approach aims to combat racism by simply declaring not to see race. The rationale is that if we are colorblind and minimize rather than attend to our differences, then racism will go away. If only it were that simple.

It does not improve our ability to navigate and ameliorate race relations to refuse to address race. In fact, the scientific research on racial attitudes and prejudice is unequivocal: the colorblind approach to combating racism is ineffective and makes the problem worse. For example, a recent study empirically demonstrated how the colorblind approach falls short. Sixty 8-11 year old students were asked to help their teacher review a storybook. One book took a valuing diversity approach (“We want to show everyone that race is important because our racial differences make each of us special”) while the other took a colorblind approach (“We want to show everyone that race is not important and that we’re all the same”). All students then listened to stories that described interactions with different levels of racial bias, including 1) no bias, 2) ambiguous, and 3) explicit bias. Researchers found that students who were taught from the colorblind perspective were less able to identify the racial discrimination and recalled the story in a way that minimized the likelihood of adult intervention. The authors conclude that, “the possibility that well-intentioned efforts to promote egalitarianism via color blindness sometimes promote precisely the opposite outcome, permitting even explicit forms of racial discrimination to go undetected and unaddressed. In doing so, color blindness may create the false impression of an encouraging decline in racial bias, a conclusion likely to reinforce its further practice and support.”

Similarly, it does not behoove us to create bullying programs and not specifically name the ways specific groups are targeted. We miss the opportunity to be effective by failing to name the elephant in the room. It is possible, that like with colorblind rhetoric, gayblind anti-bullying campaigns might reinforce and permit problematic dynamics.

Sometimes it takes seeking information and listening to experiences of people who are targeted for us to begin to understand how urgent the need is for tailored interventions. It is false and disingenuous as a member of a privileged group to paint attention towards discrimination and mistreatment of a targeted group as unwarranted or even worse reverse discrimination. In my own (Dr. Banks) work with White first year college students, I have seen significant decreases in their colorblind racial attitudes as a results of intensive sessions that increase knowledge and awareness of societal and personal issues of race. As flawed as it may be, perhaps the “It Gets Better Campaign” will have a similar affect through opening people up to the experiences different from their own. Yet one of the major criticisms of the series, is that in a way it paints bullying as inevitable. Some of the stories make it sound as if bullying is a rite of passage in high school and often condone the perpetrators as simply being victims of their cultural contexts..

Bullying is not a rite of passage. Some may disregard the recent suicides as anomalies. Yet, research indicates that bullying leads to many long term consequences. Bullying is also preventable. Some have opposed anti-bullying efforts on the premise the bullying programs don’t work. However, whole-school interventions, those that go beyond making simple changes to the curriculum to address the entire school culture, are highly effective and should be the model all schools should follow. Yet, decades of research on race and racism teach us that adopting a gayblind approach to this problem is not only unwarranted, but it may make the problem worse.

*Special thanks to my guest co-author:

Nestor L. Lopez-Duran PhD is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of Michigan. He conducts research on mood disorders in children and adolescents. He is also the editor of www.child-psych.org, a research-based blog where he discusses the latest research findings on parenting, child disorders, and child development. He can be contacted at [email protected].

Most Recent

Recent Comments

- Blog News- Left and Right Views » Race-Talk » Blog Archive » Michael Barone gets his facts wrong on Michael Barone gets his facts wrong

- Acknowledging Difference, not Defeat: A Racial Justice Perspective on the Medicaid Debate | health justice NYC on Acknowledging difference, not defeat

- Links of Great Interest: Bring Amina home! — The Hathor Legacy on In prison reform, money trumps civil rights

- Race-Talk » Blog Archive » President Barack Obama, Dred Scott: A … | Barack Obama on President Barack Obama, Dred Scott: A case of domestic terrorism

- In prison reform, money trumps civil rights « Politicore on In prison reform, money trumps civil rights

Search in Archive

Favorite Blogs

What is Race-Talk?

The Race-Talk is managed and moderated by the staff at the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity and is open to all respectful participants. The opinions posted here do not necessarily represent the views of the Kirwan Institute or the Ohio State University.

Our goal is to revolutionize thought, communication and activism related to race, gender and equality. Race-Talk has recruited more than 30 extraordinary authors, advocates, social justice leaders, journalists and researchers who graciously volunteered their expertise, their passion and time to deliberately discuss race, gender and equity issues in the US and globally.

COMMENTS